Thyroid Nodule

What is the thyroid gland?

The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped endocrine gland that is normally located in the lower front of the neck. The thyroid’s job is to make thyroid hormones, which are secreted into the blood and then carried to every tissue in the body. Thyroid hormone helps the body use energy, stay warm and keep the brain, heart, muscles, and other organs working as they should

What is a thyroid nodule?

The term thyroid nodule refers to an abnormal growth of thyroid cells that forms a lump within the thyroid gland. Although the vast majority of thyroid nodules are benign (noncancerous), a small proportion of thyroid nodules do contain thyroid cancer. In order to diagnose and treat thyroid cancer at the earliest stage, most thyroid nodules need some type of evaluation.

What are the symptoms of a thyroid nodule?

Most thyroid nodules do not cause symptoms. Often, thyroid nodules are discovered incidentally during a routine physical examination or on imaging tests like CT scans or neck ultrasound done for completely unrelated reasons.

Occasionally, patients themselves find thyroid nodules by noticing a lump in their neck while looking in a mirror, buttoning their collar, or fastening a necklace. Abnormal thyroid function tests may occasionally be the reason a thyroid nodule is found. Thyroid nodules may produce excess amounts of thyroid hormone causing hyperthyroidism. However, most thyroid nodules, including those that cancerous, are actually non-functioning, meaning tests like TSH are normal.

Rarely, patients with thyroid nodules may complain of pain in the neck, jaw, or ear. If a nodule is large enough to compress the windpipe or esophagus, it may cause difficulty with breathing, swallowing, or cause a “tickle in the throat”. Even less commonly, hoarseness can be caused if the nodule invades the nerve that controls the vocal cords but this is usually related to thyroid cancer.

What causes thyroid nodules and how common are they?

We do not know what causes most thyroid nodules but they are extremely common. By age 60, about one-half of all people have a thyroid nodule that can be found either through examination or with imaging. Fortunately, over 90% of such nodules are benign.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which is the most common cause of hypothyroidism (low thyroid), is associated with an increased risk of thyroid nodules. Iodine deficiency, which is very uncommon in the United States, is also known to cause thyroid nodules.

How is a thyroid nodule evaluated and diagnosed?

Once the nodule is discovered, your doctor will try to determine whether the rest of your thyroid is healthy or whether the entire thyroid gland has been affected by a more general condition such as hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism. Your physician will feel the thyroid to see whether the entire gland is enlarged and whether a single or multiple nodules are present.

The initial laboratory tests may include measurement of thyroid hormone (thyroxine, or T4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in your blood to determine whether your thyroid is functioning normally.

Since it’s usually not possible to determine whether a thyroid nodule is cancerous by physical examination and blood tests alone, the evaluation of the thyroid nodules often includes specialized tests such as thyroid ultrasonography and fine needle biopsy.

Thyroid Ultrasound:

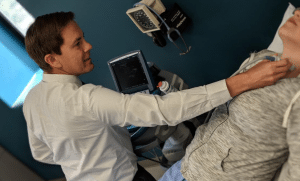

Thyroid ultrasound is a key tool for thyroid nodule evaluation. It uses sound waves to obtain a picture of the thyroid. This very accurate test can easily determine if a nodule is solid or fluid filled (cystic), and it can determine the precise size of the nodule.

Ultrasound can help identify suspicious nodules since some ultrasound characteristics of thyroid nodules are more frequent in thyroid cancer than in non-cancerous nodules. Thyroid ultrasound can identify nodules that are too small to feel during a physical examination. Ultrasound can also be used to accurately guide a needle directly into a nodule when your doctor thinks a fine needle biopsy is needed.

Once the initial evaluation is completed, thyroid ultrasound can be used to keep an eye on thyroid nodules that do not require surgery to determine if they are growing or shrinking over time.

Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy:

A fine needle biopsy of a thyroid nodule may sound frightening, but the needle used is very small and a local anesthetic may not even be necessary. Sometimes, medications like blood thinners may need to be stopped for a few days before to the procedure. Otherwise, the biopsy does not usually require any other special preparation (no fasting). Patients typically return home or to work after the biopsy without even needing a bandaid!

For a fine needle biopsy, a doctor will use a very thin needle to withdraw cells from the thyroid nodule. Ordinarily, several samples will be taken from different parts of the nodule to give your doctor the best chance of finding cancerous cells if they are present. The cells are then examined under a microscope by a pathologist.

The report of a thyroid fine needle biopsy will usually indicate one of the following findings:

- Benign (noncancerous). • This result is obtained in up to 80% of biopsies. Generally, benign thyroid nodules do not need to be removed unless they are causing symptoms like choking or difficulty swallowing. Follow up ultrasound exams are important. Occasionally, another biopsy may be required in the future, especially if the nodule grows over time.

- Malignant (cancerous) or suspicious for malignancy: A malignant result is obtained in about 5% of biopsies and is most often due to papillary cancer, which is the most common type of thyroid cancer. A suspicious biopsy has a 50-75% risk of cancer in the nodule. These diagnoses require surgical removal of the thyroid after consultation with your endocrinologist and surgeon.

- Indeterminate. This is actually a group of several diagnoses that may occur in up to 20% of cases. An indeterminate finding means that even though an adequate number of cells was removed during the fine needle biopsy, examination with a microscope cannot reliably classify the result as benign or cancer.

- Follicular lesion: The biopsy may be indeterminate because the nodule is described as a follicular Lesion. These nodules are cancerous 20-30% of the time. However, the diagnosis can only be made by surgery. Since the odds that the nodule is not a cancer are much better here (70-80%), only the side of the thyroid with the nodule is usually removed. If a cancer is found, occasionally the remaining thyroid gland usually must be removed as well. If the surgery confirms that no cancer is present, no additional surgery to “complete” the thyroidectomy is necessary.

- Follicular lesion of undetermined significance: The biopsy may also be indeterminate because the cells from the nodule have features that cannot be placed in one of the other diagnostic categories. This diagnosis is called atypia, or a follicular lesion of undetermined significance. Diagnoses in this category will contain cancer rarely, so repeat evaluation with FNA or surgical biopsy to remove half of the thyroid containing the nodule is usually recommended.

- Nondiagnostic or inadequate. This result is obtained in less than 5% of cases when an ultrasound is used to guide the FNA. This result indicates that not enough cells were obtained to make a diagnosis but is a common result if the nodule is a cyst. These nodules may require reevaluation with second fine needle biopsy, or may need to be removed surgically depending on the clinical judgment of your doctor.

How are thyroid nodules treated?

All thyroid nodules that are found to contain a thyroid cancer, or that are highly suspicious of containing a cancer, should be removed surgically by an experienced thyroid surgeon. Most thyroid cancers are curable and rarely cause life-threatening problems.

Thyroid nodules that are benign by FNA or too small to biopsy should still be watched closely with ultrasound examination every 6 to 12 months and annual physical examination by your doctor. Surgery may still be recommended even for a nodule that is benign by FNA if it continues to grow, or develops worrisome features on ultrasound over the course of follow up.

References:

American Thyroid Association